This third post about life outside the asylum ventures over the border into Devon, highlighting two cases which prompted legal processes concerning the domestic confinement and inadequate care of those considered ‘lunatics’. These legal processes demonstrate the turn towards the belief that, in the minds of the authorities at least, the best place for the ‘pauper insane’ was the County Asylum, reinforced by the Acts of 1845. And for Charles Luxmore and Edward Lancey this belief would certainly seem to have been an accurate one.

Charles Luxmore had become a blacksmith in his youth, despite being a child of ‘weak intellect’. However, in 1838, after he displayed increasing episodes of ‘mania’, his father confined him – a situation he was to endure for the next 13 years.

He was restrained with a chain and leg iron within a wooden ‘cell’ measuring 7ft x 4ft, at the family home at Germansweek, near to the Cornwall/Devon border. When his parents became infirm and unable to manage Charles, they asked John Yeo, their son-in-law, to take over. Yeo and his wife moved to Orchard [probably Orchard Barton], in nearby Lewtrenchard, taking Charles and the wooden structure with them.

A local resident reported to the Poor Law Officer their concerns that a ‘lunatic’ was being confined in poor conditions, and Charles was discovered. He was found chained to a beam, naked and filthy. Unable to walk without assistance, he was taken by covered cart to the Devon County Asylum at Exminster, which had opened in July 1845 – 7 years into Charles’s confinement.

This was a complicated case, as it was not immediately apparent how the law had been broken. It was finally decided Yeo should be prosecuted for volunteering to take care of a lunatic but failing to do so. The case was heard in July 1851. Yeo was sentenced to 6 months in prison – although in a common gaol rather than a punitive house of correction – with the clear message that people should report to the authorities if they were unable to humanely care for a family member within the home. The new asylums were the places to manage and treat insanity.

Nevertheless, many families resisted placing their relatives within the County Asylums.

Devon County Asylum at Exminster

Image: The Time Chamber

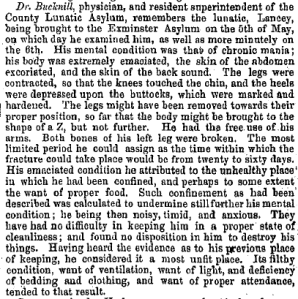

The second Devon case involved Anthony Huxtable, charged with ‘abusing, ill-treating, and wilfully neglecting Edward Lancey, a lunatic’ at Bratton Fleming, near Barnstaple.

Edward, Huxtable’s brother-in-law, had been discovered after a ‘holloaing noise’ was heard coming from the house by James Richards, the relieving officer of Barnstaple Union. Edward was found in a darkened room, measuring 8ft x 6ft, and less than 6ft high, which could not be opened from the inside. The window was boarded, and, despite it being only 6ft from the family sitting room and opposite the kitchen door, the room emitted a ‘great stench’, attributed to it having no ‘convenience’.

James Richards described how he saw ‘something like a bundle moving about on the bed’. Taking a closer look he realised ‘it was a human being’. Edward was on a bed covered in straw, with just a piece of unidentifiable cloth as bedding, and wearing only a shirt.

‘I could not see much of the lunatic in the bed’, continued Richards, ‘but from what I did see, I remarked that his legs were drawn up, and his nose was almost between his knees’. Lancey would not – or could not – give Richards rational responses, only talking to himself, and appeared ‘wholly without intellect’. Richards requested ‘some clothes for the lunatic’, but Huxtable stated he did not have any. When Richards threatened to take ‘the lunatic’ to the magistrates at Barnstaple naked, Huxtable found some clothes, although from his ‘bent, fixed position’ Richards supposed it would be impossible to clothe Lancey in trousers. Indeed, he observed, ‘when he was carried out of the house into the omnibus, he retained the same position in which he had been lying’.

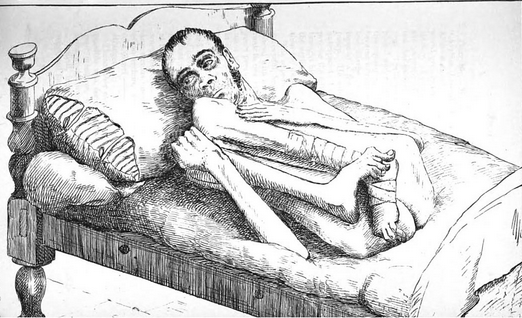

Edward Lancey, a few days after his admission into Devon County Asylum, by G. Pycroft, published in The Asylum Journal of Mental Science Vol. II (1856)

Edward’s terrible condition and rescue was widely reported in the newspapers, as was Huxtable’s subsequent trial. It transpired Huxtable was a widower who ‘did not wish to part with the lunatic, as his (lunatic’s) mother and sister wished to keep him’. Huxtable was in receipt of £21 a year to keep Lancey: £7 from his wife’s estate, and £7 each from that of her two sisters, also deceased. Edward had been with him for 7 years, and Huxtable described him as ‘perfectly quiet and harmless’. Previously Lancey had lived with his mother – the intimation being she may also have been ‘insane’ – and Huxtable testified that Edward was:

‘in the same crippled, helpless condition when he came to him; that he was exceedingly filthy in his personal habits; and that it was impossible to prevent him’.

Huxtable also claimed that Edward ‘destroyed his clothes as fast as they were given to him’.

Speaking at the trial on Huxtable’s behalf was the rector of the adjoining parish, Reverend Carwithen. He testified that Huxtable was industrious, hardworking, and of excellent character. Carwithen had visited the property and heard Lancey ‘raving’: he had also smelt the ‘intolerable’ and ‘offensive’ stench. Huxtable had assured Carwithen he tried to keep his brother-in-law clean, but any ‘convenience’ placed in the room had been destroyed.

Mr. Torr, the surgeon called to the property at the request of Richards, reported he had found him to be pale and emaciated, with his ‘knees up to his face’, unable to use his legs to walk. However, he also observed Lancey had been on clean oat straw with no bedsores or marks of violence. Huxtable informed Torr he had not put him in an asylum as none would take him due to his ‘dirty habits’ – an assertion refuted by Torr who told him ‘there were places provided for them’.

Edward was removed to the Devon County Asylum, where John Bucknill, the superintendent, examined him. Bucknill reported that whilst he had seen ‘persons kept in farm houses’ they were ‘not in the filthy condition as was this lunatic’. He took the opportunity to emphasise the benefits of the asylum, attributing many aspects of Lancey’s condition as due to, or exacerbated by, his previous confinement, and highlighting how his condition had improved with proper food, care, and a larger, well-ventilated room.

In a judgement shocking to modern sensibilities, Huxtable was acquitted, as he had not imprisoned Edward, ‘the lunatic being himself, by very nature, a prisoner’, whilst the charge of wilful neglect was dismissed as it was ‘more accountable to ignorance and the incapabilities of the farmer’s house’. The evidence was thought to show Huxtable had done all he could for Lancey under the circumstances – and to usefully demonstrate the undeniable benefits of the County Asylum.

Bucknill published an account of Edward Lancey’s case, to underline precisely that, drawing attention to another recently admitted patient called Joseph Adams. Joseph had been discovered in an attic room where he had been confined by his mother and brother for 18 years. In that time he had never been out of the room nor had clothes on – although Bucknill notes he was well fed and not crippled.

Nevertheless, despite the promotion of the benefits of the County Asylums, mistrust, combined with financial and geographical factors, meant the workhouse continued to be used to house the pauper insane throughout the 19th century.

References and further reading:

Sarah Wise, Inconvenient People: Lunacy, Liberty and the Mad Doctor in Victorian England (2012)

Elaine Murphy, ‘Workhouse care of the insane, 1845 – 90’ in Pamela Dale and Joseph Melling (eds) Mental Illness and Learning Disability Since 1850: Finding a place for mental disorder in the United Kingdom (2006) pp. 24 – 45

Leonard D. Smith, ‘The County Asylum in the Mixed Economy of Care, 1808 – 1845’ in Joseph Melling and Bill Forsythe (eds) Insanity, Institutions and Society, 1800 – 1914: A social history of madness in comparative perspective (1999) pp. 33 – 47

Further Report of the Commissioners in Lunacy, to the Lord Chancellor (1847)

‘Cruel Treatment of a Lunatic’, Medical Times & Gazette Saturday, January 13 1855, p. 559

‘Cruel Conduct Towards a Lunatic’, The Standard Tuesday May 29 1855

‘Alleged Ill-Treatment of a Lunatic’, Trewman’s Exeter Flying Post or Plymouth and Cornish Advertiser Thursday July 261855

‘Seven Years in a Lunatic’s Life’, Lloyds Weekly Newspaper Sunday, June 3 1855

John Charles Bucknill (ed) The Asylum Journal of Mental Science Vol. I (1855)

John Charles Bucknill (ed) The Asylum Journal of Mental Science Vol. II (1856)

The Time Chamber: http://www.thetimechamber.co.uk/beta/sites/asylums/asylum-history/asylum-architecture

Devon County Mental Hospital: Social Attitudes and Mental Illness in Devon 1845 – 1986: http://dcmh.exeter.ac.uk/