Staff Canteen. © M. Hodgson 2013. All rights reserved.

H. G Woods, Charge Nurse from 1919 – 1949 described memories of mealtimes in Charles Thomas Andrews’ book on the history of St Lawrence’s, The Dark Awakening (1978):

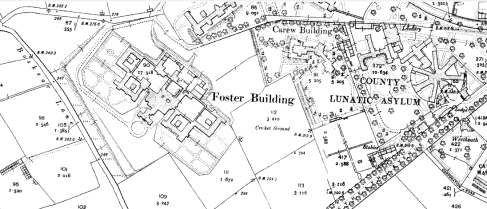

‘The diet was revolting: it even shocked those of us who had just returned to civilisation after four years of active service and were not easily shocked. Breakfast was at 7.30 a.m. The majority of the patients ate in Foster Hall where they would find the tables laid out with a large desert spoon and a basin to each place accompanied by a half pound hunk of bread smeared with the cheapest of margarine. There was porridge, for those who could eat it, served in the basins and, when the porridge was consumed the same basin was filled with about one and a half pints of cocoa. To patients who worked on the farm or on the grounds or garden there was fried rusty bacon and potatoes.’

He continues:

‘As most of the food that went to make up the dinner was produced on the farm and in the hospital the standard of dinners was somewhat higher, but tea at 5p.m. was back to the low standard of breakfast – weak tea served in basins and the half pound slice of bread smeared with margarine. This was the last meal of the day for some years: the patients had nothing more until 7.30 a.m. the next day. After some years this was supplemented by an allowance of bread and cheese, for working patients, for supper at 7 p.m.’

He observes the changes over time:

‘As time went on conditions for the patients became better especially as some of the older administrators retired and we were controlled by younger and more enlightened personnel. Food improved, especially the serving of it; we progressed from basins to soup plates, then to mugs and from mugs to cups and saucers, from mess room to ward messing which was a great advantage in many ways. In ward 8 we were now allowed to prepare our own bread and margarine after a battle so, instead of slicing half a loaf into four slices, we cut it into fourteen slices and the patients were very appreciative’.

Staff Dining Room Information. © M. Hodgson 2013. All rights reserved.

Gordon R. Retallick, a nurse who started working at St Lawrence’s on April 27 1929, remembers having his meals on the ward:

‘we had a roast dinner every day of the year. Our rations consisted of half a pound of sugar, half a pound of butter and half a pound of bacon weekly and a small loaf of bread every alternate day […] On night duty we brought our own food and ate it in the dormitory when convenient, during duty hours.’

Gordon worked at St Lawrence’s for 41 years. Of patient mealtimes he recalls:

‘Before patients were allowed to leave the dining room, all knives, forks and spoons were checked and, if found not correct, no one was allowed to leave the table until the missing piece was found. This sometimes meant searching the patients. The charge attendant always said grace before the patients dispersed’.

Eileen Goff, who spent 24 years at St Lawrence’s, a ward sister for 12 of these, also had her memories of mealtimes recorded in The Dark Awakening:

‘Meals were very poor for both patients and staff during the war years and some dreadful looking brawn, a horrible pink colour with even black bristly hair showing in the horrible looking concoction, was served at least once a week. Night nurses went on duty with a last meal served in the dining room at about 7.15 p.m.; then they had no further meal until breakfast at 7 to 7.30 p.m. next day when they came off duty’.

Milk Machine. © M. Hodgson 2013. All rights reserved.

Robert Rowe, Assistant Chief Nurse who worked at St Lawrence’s for 36 years, from 1919 to 1955, remembers breakfast being at 8 a.m.: ‘Staff when to breakfast in relays, some had to have their meals in the ward with the patients’. Dinner was at noon, with tea at 4.30 p.m.: ‘This, the last patients’ meal of the day, consisted of two slices of cake with bread and margarine’, although stating that aside from this meal, the patients’ food was ‘generally very good’. However, ‘There was no canteen or any other facilities for obtaining food in the institution’. He noted the improvements made under Mrs. Belinda Banham, as Chair of the Management Committee (and who wrote the Preface in The Dark Awakening) during the late 1960s and early 1970s:

‘Under Mrs. Banham’s administration we have noted what progress has been made. The food and furnishings, the wellbeing and care of the patients is excellent. Both my wife and I expressed the view that we wouldn’t mind spending a month’s holidays at St. Lawrence’s. The old 20 foot long bare tables with basins for tea have gone: it is now a first class hotel service’.

© M. Hodgson 2013. All rights reserved.

These recollections contrast with the diet during the early 1820s, on the opening of the Cornwall County Asylum, devised by Dr Richard Kingdon. There were three meals a day, and the typical menu consisted of:

Morning: milk, meat broth or gruel and bread

Midday: baked or boiled meat and potatoes with seasonal vegetables, or soup with vegetables and bread. Sometimes there would be ‘good broth’, pea soup or rice milk, with pudding on a Wednesday

Evening: bread, cheese or treacle, or bread and milk, sometimes there would be seedcake or broth.

The Committee approved this menu on August 17th 1820, but added in the following stipulations. Beer, cider or wine was to be served ‘when required’, and dinners were to vary, with fish to be given ‘occasionally’. There was to be a good supply of seasonal vegetables, such as carrots, parsnips and turnips, with sweetened peppermint and other herb teas to be given to the women for their supper with seedcake. There was also to be a sick diet, ‘to such as require it, all in such quantities as to improve the general health’. Tea and coffee, however, were too expensive, and did not form part of the patients’ diet.

© M. Hodgson 2013. All rights reserved. All ward kitchens had a pig bin, with the swill picked up regularly by truck.

The initial furnishing orders for the old Cornwall County Asylum in 1820 reveals the following for the kitchen:

2 dozen wooden plates, bowls and spoons, Bethlem pattern of sycamore, and 8 trays

2 dozen knives and forks,12 iron spoons and a soup ladle

24 ewers, 8 pewter dishes from 20 – 26″ in diameter and 12 pewter plates

a digester

a 5 gallon boiler and a 2 gallon copper tea kettle

a fish kettle, a frying pan and 4 iron saucepans of different sizes

2 pepper boxes, a coffee and pepper mill

2 flour dredgers, 2 collanders, a cleaver, meat saw and chopping block

2 morestone salting vats, 2 buckets and a time piece

a gridiron.

The latter – a gridiron – is of some significance, being associated with the martyrdom of St Lawrence himself.

St Laurence, or Lawrence, with gridiron.

Ranworth Rood Screen, c. 1430, St Helen’s Church, Norfolk.

Photograph: Martin Harris

Badge depicting St Lawrence holding a gridiron. © M. Hodgson 2013. All rights reserved.

And for a picture of dining in Foster Hall from the 1950s/60s – see: http://slhphotosbodmin.blogspot.co.uk/2013/10/bygone-foster-hall.html?spref=fb

With sincere thanks to M. Hodgson, Steve Davies RMN (Registered Mental Nurse) and the St Lawrence’s Facebook Page.

Please check out https://www.facebook.com/britainabandoned

and https://www.facebook.com/stlawrences.hospital?fref=ts

References:

C.T. Andrews, The Dark Awakening: A History of St. Lawrence’s Hospital (1978)

Cornwall Lunatic Asylum Minutes, August 17th 1820