Cornwall County Asylum today

© Examining Mental Illness in Cornwall 2013. All rights reserved.

Some families could afford a private keeper and manage their relatives at home, or lodge them in single houses under the care of an attendant. However, many were confined in the family home. Families were exempt from official scrutiny when caring for relatives who were mentally ill or had a learning disability, as, particularly prior to the County Asylum Act of 1845, this was understood as wholly appropriate, and in some cases a legal obligation.

Newspapers and reports of the time sometimes provided a tragic glimpse of this arrangement, bringing to public attention incidences when care at home was woefully inadequate.

For example, on April 7th 1810 the West Briton reported that the previous Monday Thomas Hunkin of Megavissey, a married man with five children, had hung himself ‘in a small room in which he had been confined for some time, in consequence of his evidencing symptoms of derangement’.

This news was published less than two weeks after the paper had informed its readers how the High Sherriff, gentlemen, freeholders, clergy, and ‘other inhabitants of the county of Cornwall’ had assembled at Bodmin Assizes to discuss ‘the expediency and propriety of providing a lunatic asylum, or house for the reception of lunatics, and other insane persons’ within Cornwall. Local magistrates were subsequently requested to ascertain the numbers of people within their districts ‘for whose accommodation, comfort and cure it will be necessary in the first instance to provide’.

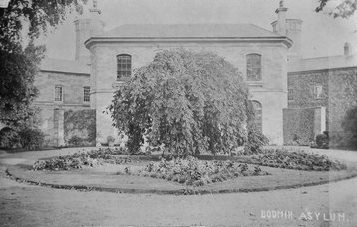

Bodmin Asylum

Image: Old Cornwall in Pictures

The founding of the County Asylum was primarily to address the issue of the pauper insane, for whom the inadequacies of home care – and within the poorhouse and workhouse – could prove fatal. Another case, reported on December 25th 1812 was that of ‘a poor but once industrious man’, Hannibal Thomas of Chacewater, who for two years previously had ‘laboured under that most dreadful of maladies, mental derangement’. His wife and five young children had been supported by the parish, but it was only when one of the children died that ‘the deplorable state of this miserable family was discovered’.

Living in a single room, Hannibal was found:

‘confined to the bed, raving in all the wildness of frenzy; the mother also was confined by illness, and near her lay the corps of her infant; and the other children crying for food, which their wretched parent was unable to supply, their pittance not enabling them to secure a sufficiency of barley-bread or potatoes’.

There was a public appeal for charity for the family.

Wrist Restraint

Image: Science Museum, London

Poorhouses or workhouses were often the only options for families in poverty when they could no longer manage their relative in the family home. A report on the 28th February 1817 provides another vivid illustration of the dire circumstances these families could find themselves in. A nineteen year old woman ‘subject to fits and occasional derangement’ was removed to a pauper house in St Buryan ‘because the overseers thought two shillings a week too much for her maintenance; her father is an industrious fisherman with a large family; her mother is blind’.

However, a fire reduced some of the St Buryan pauper houses to ruins: 21 of the 27 parish poor managed to escape by jumping from the windows: this young woman was amongst those who perished. Separated from her friends upon being removed to the poor house she had become violent, and been secured by a chain:

‘She was seen struggling in the flames but could not free herself from the fetters, and no assistance could be afforded her’.

Restraint Harness

Image: Science Museum, London

Care at home for those understood as mentally ill or mentally impaired did not necessarily mean confinement. On 25th February 1833 James Symons, ‘of weak intellect’, from Praze in Crowan parish, was missing, ‘supposed to have missed his road, in following his father to work, at a mine’, and ‘to have wandered beyond his knowledge’. A month later a report appeared in the West Briton, and during that time he had only been heard of once, at the beginning of March:

‘when he was found at Mawgan, and was put back to Michell, by a parish officer, who, it is believed, supposed he would find his way home; but his friends have not since that time – about the 4th instant – heard any intelligence of him.’

Symons was described as 5 foot 4 inches, ‘about 26 years of age’ and ‘slight made’, with dark hair and ‘reddish whiskers’. He was ‘of reserved habits; talks to himself, and is capable of telling his name and the place of his residence’. At the time of his disappearance he had been wearing a blue-striped shirt, with a neckerchief and blue and white socks, a blue jacket, a waistcoat and trousers of heavy material (fustian), ‘high shoes, and an old hat’.

‘Whoever may meet the person above described’, the paper stated, ‘are requested to restore him to his afflicted parents, for which a handsome reward will be given.’ Sadly, however, Symons was reported as still wandering nearly 7 months later, although the September 6th edition of the West Briton did report receiving information ‘that the poor lunatic was seen in the neighbourhood of Liskeard, about a month since’. ‘As he is not capable of inquiring his way’ the paper continued:

‘it is earnestly requested, by his distressed father, that he may be detained by any person who may meet with him, and information be sent, by post, to Mr John Symons, Praze, Crowan, who will immediately proceed to take him home, and who will pay all reasonable expenses incurred’.

It is not clear whether poor James Symons made it home.

References and Further Reading

West Briton

Old Cornwall in Pictures: https://en-gb.facebook.com/OldCornwallInPictures

R. M. Barton, Life in Cornwall in the Early Nineteenth Century (1997)

Sarah Wise, Inconvenient People: Lunacy, Liberty and the Mad Doctor in Victorian England (2012)

Joseph Melling and Bill Forsythe (eds) Insanity, Institutions and Society, 1800 – 1914. A social history of madness in comparative perspective (1999)

Science Museum: http://www.sciencemuseum.org.uk/broughttolife/objects/display.aspx?id=92676; http://www.sciencemuseum.org.uk/broughttolife/objects/display.aspx?id=92687. Wrist restraint and restraint harness: these items appear to be replicas made after 1850.